by Justin Schlosberg

Time for a review of impartiality rules during elections?

It is frequently said that a free media is the cornerstone of a healthy democracy and none more so than during an election period. But democracy is only well served if all political views are given equal prominence and fair interrogation. We know we have a partisan press but during this election period, TV coverage also stands accused of amplifying press bias.

Research published by Loughborough University has shown that during the first two weeks of the campaign, Labour attracted by far the most negative coverage in the national press of all the major parties. The Conservatives on the other hand, unequivocally got the most favourable coverage. We might expect that, given that most national newspapers (including the three largest titles across both print and online) have endorsed the Conservatives during successive recent elections.

The key question for our democracy is how far broadcasters – which reach across partisan audiences – correct or amplify this imbalance. This question is particularly acute when it comes to the BBC, since its audience reach far eclipses that of its rivals both on air and online.

Unlike newspapers, broadcasters are subject to impartiality rules – and particularly strong ones during election periods. One obvious way in which they amplify press imbalance is in the regular slots given over to reviewing the papers, often recurringly on prime time flagship programmes like BBC One’s Breakfast TV or Radio 4’s Today Programme.

But at face value, presenters and journalists seem to give the major parties an equally tough grilling. There’s certainly no evidence to suggest they are particularly lenient in interviews with one side or the other. The Loughborough research also shows that when it comes to news access, broadcasters are stringently careful to afford a balanced platform – at least between the two major parties.

Issue ranking for health, environment and economy: polls versus TV

| Yougov Polling | TV election coverage | |

| HEALTH | 2 | 4 |

| ENVIRONMENT | 3 | 6 |

| ECONOMY | 3 | 2 |

Source: Yougov Issue Tracker, Loughborough University

But it’s when we dig into issues that we start to see how broadcasters – and the BBC in particular – have systematically mirrored, and in some aspects intensified skews in the press coverage. According to the Loughborough research, other than the electoral process it was Brexit that dominated TV coverage during the first two weeks of the campaign, even more than it did the press agenda. This was followed by the economy. These are the two issues that have been most prominent in Conservative campaign rhetoric whilst health and the environment is where Labour has been pressing its campaign messages. These were the fourth and sixth most covered issues on television. Yet according to weekly issue polling done by Yougov, the public has consistently ranked health as the second most important issue facing the country at this time, considerably more so than the economy. And the environment has polled more or less on a par with the economy.

When we drill further into issues, the imbalances in favour of Boris Johnson’s Conservatives appear even more striking. During the first two weeks of the campaign, there were almost identical pairs of stories involving two Conservative candidates and two Labour candidates who were suspended or forced to resign over alleged antisemitic comments made on social media. We examined a sample of online coverage that included all national newspapers and broadcasters, as well as all scheduled TV bulletins and news programmes on BBC One, BBC Two, ITV, Channel 4 and Sky. Surprisingly, there were virtually equal number of headlines focused on the Labour candidates versus the Conservatives (14 and 15 respectively). But on television, the Labour candidates were three times more likely to be mentioned. And when the Chief Rabbi intervened by accusing Labour of harbouring rampant antisemitism, it was a lead story across television news, far eclipsing a statement made on the same day by the Muslim Council of Britain which was a scathing attack on Islamophobia in the Tory Party.

But there is another still more important way in which television has distorted the debate during the campaign so far. This becomes clear when we examine the disproportionate spotlight given to dissenting voices within Labour and Conservative parties. Early on in the campaign, former Labour MP Ian Austin made headlines in endorsing the Conservative Party, so much so that during the first week of the campaign he was the sixth most prominent politician featured on television, more than both Jo Swinson and Nicola Sturgeon, as well as most other cabinet and shadow cabinet figures (according to the Loughborough University research). In contrast television news programmes barely covered Ken Clarke – a far more recognisable figure from the Conservatives – who made a similar announcement (at a similar time) that he would not be voting for the Tories.

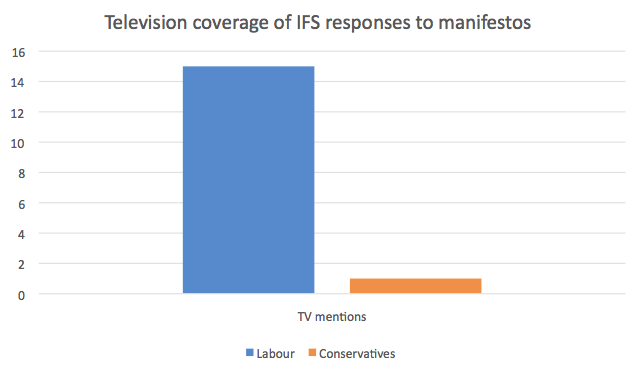

When it comes to independent critical voices, the most striking imbalance was in the coverage of manifesto launches. The Institute of Fiscal Studies produced an immediate and strongly critical response to both the Tory and Labour manifestos, accusing Labour of being unrealistic in its assertion that only the top five percent of earners would be impacted by its tax and spending plans, and accusing the Tories of trying to have their cake and eat it by its ‘triple lock’ on tax. Remarkably, the IFS response to Labour was covered 15 times in the two days following its manifesto launch compared to just once in the two days following the Conservative manifesto launch.

Even if we factor in mentions of an earlier IFS rejection of Boris Johnson’s claim that earners will be £500 a year better off under the Tories’ plans for national insurance, television news still paid nearly four times more attention to IFS critique of Labour’s costings overall.

We might know what to expect from a partisan press, but television news in general has been the more trusted news source. Since the Ofcom guidance notes state that “[d]ue impartiality can be achieved over a period, for instance a General Election period in “clearly linked and timely programmes”, we might expect election coverage to now take a turn to the left. But something tells us this is unlikely. Whatever the outcome, the time for a close review of the TV news impartiality rules is surely due?

Note: the television sample consisted of all scheduled news programmes and bulletins on BBC One, BBC Two, ITV, Channel 4 and Sky (except round-the-clock bulletins on BBC News Channel and Sky). The online sample consisted of all national newspaper websites plus Metro, Evening Standard, Huffington Post, Buzzfeed, BBC.co.uk, News.sky.com and ITV.com/news.