By Justin Schlosberg

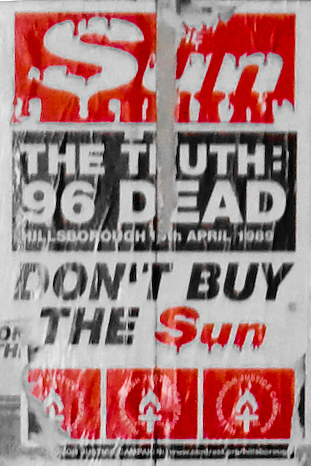

What do Michael Gove and Jeremy Corbyn have in common? For one thing (and perhaps the only thing), they both believe that the mainstream media – and particularly the right wing national press – no longer hold sway over elections. And they are not alone in holding such views. Few doubt that we are witnessing a profoundly disruptive moment for the consensus that has shaped mainstream media and political debate for decades. The 2017 election results were a far cry from those of the last general election in 2015, or the EU referendum in 2016, which seemed only to confirm the enduring influence of the right wing press. In the space of 12 months we have moved into a new era where political news sources on social media are now dominated by an emergent leftist ‘fifth estate’ led by websites like the Canary and Evolve Politics; where there is evidence of a growing consciousness of mainstream media bias against Labour – and Jeremy Corbyn in particular – amongst voters across the political spectrum; and where videos of activists ripping up copies of the Sun newspaper in the wake of the Grenfell Tower disaster are going viral.

So it’s easy to see why so many journalists and commentators have finally called time on the mainstream media paradigm and particularly newspaper influence, with George Monbiot declaring the election a “crushing defeat” for the “billionaire press”. Experts and analysts have joined in the clamour, proclaiming it was “the Sun wot lost it”, whilst the Tory campaign’s out-dated logic of media management has been widely cited as the chief cause of their disastrous poll results.

But as tempting as it is to celebrate the demise of the press baron and corporate media era, to do so not only overlooks the complexities and convergences in mainstream media power today, but plays directly into the hands of the “billionaire press” themselves.

For a start, there is nothing especially new or unfamiliar in this refrain, just as there is nothing particularly new about declining newspaper circulations (a trend which began in earnest in the 1960s). For decades, every new media phenomenon from the emergence of television to web 2.0 has spelled, for many, the end of print news and the withering of press power. And some of the leading and loudest exponents of this narrative have been none other than the owners of major newspapers themselves.

After the Sun infamously claimed credit for the Conservatives’ 1992 election victory, declaring “t’was the Sun wot won it”, the paper’s then editor allegedly faced a “hell of a bollocking” from his boss. In Rupert Murdoch’s own words, “it was tasteless and wrong for us. We don’t have that sort of power”.

This sentiment found an echo in representations by 21st Century Fox – Murdoch’s film and broadcasting arm – which is currently pushing for regulatory approval of its proposed buyout of Sky. Earlier this year the company told the government that “plurality has increased in recent years” thanks to the “transformation of news provision and consumption brought about by the internet and social media”.

According to this widely shared logic, we have reached a promised land of media abundance, where a burgeoning ‘plurality’ of channels and titles has made ownership and control of the media irrelevant and the gatekeeping power of editors obsolete. The Guardian’s Peter Preston went so far as to declare that the election “proves that media bias no longer matters”, a perspective that has long underscored arguments against the modest proposals for press regulation reform put forward by Lord Leveson, as well as arguments in favour of repealing the last remaining limits on cross-media ownership.

But what both the traditional media moguls and apostles of digital openness tend to ignore are the particular ways in which agenda control is consolidating in the new information environment. According to research by Ofcom, for instance, most news consumers in 2016 relied on 2 or fewer wholesale sources and less than they did in 2011 (when Murdoch first attempted to buy out Sky through his News Corp arm, a bid that was withdrawn amidst the fallout from the phone hacking scandal embroiling his newspapers).

As for the BBC – still by far the dominant source of news across broadcasting and digital platforms – study after study has demonstrated its tendency to reinforce rather than check the agenda power of the mainstream and right wing press in particular. Whilst the likes of the Canary may have honed the art of clickbait journalism, it is still nothing compared to the amplification enjoyed by its newspaper rivals on the BBC’s round the clock segments devoted to ‘the papers’. At the same time, Google’s news algorithm patent updates and Facebook’s ‘curating’ experiments say more about their growing deference to mainstream media agendas than support for the ‘long tail’ of niche or alternative sources.

The explosive growth attributed to the leftist online press over recent months also pales into insignificance when we consider actual page views (i.e. article reads) rather than just shares. According to this measure, 8 out of the top 10 news websites are owned by traditional newspaper groups, the majority of whom are Conservative-leaning. The reality is that the reach of websites like the Sun and Mail is still several hundred times that of the Canary, and there is little prospect of that gap being even marginally narrowed any time soon.

So whilst the bubble may be expanding, it is still a bubble, outside of which millions of voters – and not just those offline or within older age groups – remain relatively disconnected and unaffected. Celebrants of declining press power also gloss over the fact that much of the online activism and social media support base for Corbyn’s Labour was alive and kicking throughout the pre-election period, when the party’s polling was consistently at its lowest ebb in recent memory.

So what changed? For one thing, the only two traditional Labour-supporting newspapers – the Guardian and the Mirror – promptly dropped their strident opposition to Jeremy Corbyn and rallied behind the Labour leadership for the duration of the election campaign. As for broadcasters, the unveiling of election manifestos combined with special election rules on impartiality meant that for the first time since Corbyn assumed the Labour leadership, reporting on the party was (for a moment at least) focused on policies rather than personalities.

But the truth is we simply don’t know how influential different sections of the media were during the election. The question of media influence has dogged scholarly inquiry for decades and remains deeply unresolved. Every assumption about media effects (eg t’wos the Sun that lost the Tories’ majority) can just as plausibly be held in the inverse (t’wos the Sun that saved the Tories from a humiliating election defeat). We can only imagine, for instance, what the election results would have looked like had the Mirror, Guardian, Independent and Huffington Post been more or less positive in their coverage of Labour, or if the Sun, Telegraph and Mail had been less vicious in their attacks.

What we do know is that the established media continue to enjoy a uniquely wide reach across platforms. Regardless of questions about influence, the quality and balance of their coverage remain prescient and urgent issues. Their agenda power has been no more neutralised by the fifth estate, than state secrecy and surveillance has been neutralised by hacktivism. Resisted yes, but far from defeated.