Ofcom’s latest report to the Secretary of State makes clear – contrary to the claims of major media corporations like 21st Century Fox – that plurality concerns remain significant in the digital media environment. We therefore welcome Ofcom’s recommendation that there should be no further relaxation of existing media ownership rules or dilution of the public interest test regime that governs significant media mergers.

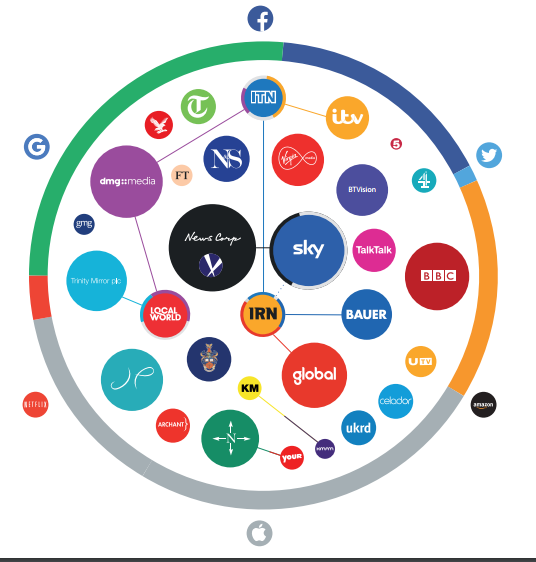

However, implicit in Ofcom’s response seems to be an assumption that the status quo of media plurality in the UK is acceptable. Such an assumption does not take account of the very real and in some ways intensifying concentration of media power that exists across the news industry. Ofcom’s own evidence shows that just three groups account for roughly half of all news consumption across platforms. If anything, this measure understates levels of concentration as recently highlighted by the Competition and Markets Authority. What’s more, studies have shown the enduring influence of right-wing newspapers over the news agendas adopted by broadcasters, including the BBC. And last month, we published evidence of a ‘disinformation paradigm’ that was prevalent across the liberal-conservative media including the BBC and the Guardian. There is no question that such evidence is inconsistent with any notion of a healthy plural media landscape.

Ofcom’s report also recommends that plurality reform should be considered in conjunction with other areas of media policy development, including the recommendations of the on-going Cairncross Review into the sustainability of ‘high quality’ journalism. We have long advocated for a more holistic approach to regulation that takes account of the various interconnected issues that impact on plurality (including sustainability and funding, ‘must carry’ rules and net neutrality). However, it is imperative that policymakers do not lose sight of the centrality of ownership to plurality concerns. We are witnessing a rapid consolidation of the news industry – especially at the local and regional level – which is putting control of newsgathering and production in progressively fewer hands. Whatever policy recommendations are made in respect of related issues, there can be no meaningful and progressive reform of media plurality until ownership concentration is redressed.

Finally, we note that Ofcom makes no mention of the regular plurality reviews it recommended in 2010, and which were subsequently endorsed by the Leveson Report, the Lords Select Committee on Communications and the government itself. It is an obvious and striking limitation of the current public interest test regime that it only operates in response to media mergers. As Ofcom has acknowledged, ownership concentration is not just a function of merger activity. A plurality regime that takes no account of dynamic and organic changes in technology and markets that can produce further concentration is simply not fit for purpose in a post digital media world.