by Justin Schlosberg

This week we learned lessons in crisis management given by Tony Blair to former News of the World editor Rebekka Brooks, at the height of the phone hacking scandal. Accordingto Brooks, the former Prime Minister advised her to set up an independent inquiry that produces a ‘Hutton style report’. This reference to the widely-discredited whitewash that saved Blair’s own political skin is not without irony. Nor is the apparent suggestion of a pre-determined outcome that will “clear” Brooks but require the acceptance of “shortcomings”.

Hutton marked the first of a string of high profile public inquiries into alleged corruption within the heart of the British power elite which produced relatively low impact outcomes. Ultimately, they have served only to leave more indelible stains on the integrity of British democracy than the events and misdeeds that produced them.

A member of the discredited Widgery tribunal which absolved British security services in the Bloody Sunday Killings, Lord Hutton was seen by many as a government ‘stooge’ from the outset. Such suspicions were underlined when his report in 2004 awarded the government a near complete vindication in its handling of David Kelly – the government weapons analyst who was found dead shortly after being ‘outed’ as the source of a controversial (though by and large accurate) BBC news report. The report insinuated that Blair had lied in his attempt to build a case for war in 2003 and the BBC was wholly castigated leading to the unprecedented resignation of its two most senior figures.

Even more worrying than the BBC’s complete capitulation in the face of state pressure was the failure of the media at large to properly scrutinise the actual cause of Kelly’s death. Evidence emerged at the inquiry casting doubt over official explanations of death by arterial bleeding, which were widely accepted without question by the news media. This included the testimonies of two paramedics who had examined the body and maintained hat the levels of blood at the scene were inconsistent with this type of death. A campaign was subsequently launched by a group of senior medical and legal experts who argued that evidence for the accepted cause of death was unsatisfactory. More importantly, they argued that the inquiry itself had not properly dealt with the cause of death and the government’s refusal to hold an inquest or release medical and police documents was an obstruction of due process.

Show Trials

The anti-climax of the Hutton Inquiry appeared to repeat itself in the Butler Review which followed shortly after. Unlike Hutton, Butler’s remit was to focus on the intelligence failures which underpinned the Iraq War controversy. But although it criticised the intelligence services for not properly verifying and corroborating sources, it was greeted by the London Evening Standard newspaper as a “Whitewash part Two” (14 July 2004) and both the main opposition political parties withdrew from the inquiry due to its restrictive remit. A particular point of contention was the appointment of Ann Taylor to the inquiry committee, a member of the team that actually produced the controversial dossier which served as a basis of the government’s case for war.

Like Hutton, Butler left a vacuum of accountability for the mistakes and alleged crimes made by politicians and it was this void which the Iraq War Inquiry – chaired by Sir John Chilcott – was intended to fill. It was also what made this third and most wide-ranging inquiry so controversial from the outset. It was announced in 2009 shortly after Tony Blair had given way to Gordon Brown as Prime Minister. Hearings were intended to be held in private but this decision was reversed following public outcry and outrage on the part of journalists and the political opposition. Strong criticism also followed the appointment of committee members by the government. Much like its two prequels, the Iraq War Inquiry was seen by many as an ‘establishment stitch-up’, the words used by David Cameron shortly after it was announced.

It is the legal incapacities of such public inquiries which render them, in the eyes of many, mere ‘show trials’: opportunities to air public grievances and cast a spotlight on the powerful without actually resulting in meaningful sanction, reform or justice. It is significant in this respect that all three Iraq-related inquiries were set up on a non-statutory or ‘ad hoc’ basis. This effectively gave the government even greater discretionary power over the scope and conduct of the inquiries than that provided for under the 2005 Inquiries Act. In the Iraq War Inquiry, disclosure of evidence was further circumscribed by the ’29 October Protocol’ which governed the Inquiry’s treatment of sensitive written and electronic information. This brought the full force of Britain’s extensive secrecy laws to bear on the inquiry, restricting the release of documents even on the basis of commercial sensitivity.

Nearly three years after it stopped taking evidence, five years after it was announced by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, and even longer since those under scrutiny left political office, Chilcott is still yet to publish his report. The reasons for the delay, not surprisingly, centre on a long-running dispute over the disclosure of ‘sensitive’ documents – specifically, those relating to crucial private correspondence between Tony Blair and US president George Bush during the run up to the war. Chilcott made the following statement on the Inquiry’s official website as early as January 2011:

Justin Schlosberg is a media activist, researcher and lecturer at Birkbeck, University of London, and author of Power Beyond Scrutiny: Media, Justice and Accountability.

There is one area where, I am sorry to say, it has not been possible to reach agreement with the government. The papers we hold include the notes which Prime Minister Blair sent to President Bush and the records of their discussions […] The Cabinet Office did not agree this disclosure.

Untold Stories By the time Tony Blair made his second appearance at the Iraq War Inquiry in January 2011, the story was already yesterday’s news. Yet just two months earlier, US diplomatic cables made public by Wikileaks and the Guardian suggested that the government had deliberately undermined the inquiry in order to protect its security relationship with the US. According to one communique which emerged on the third day of what became known as ‘Cablegate’, UK officials had “put measures in place” to protect US interests in regards to the inquiry. The news value of this cable, both in terms of new information and public interest weight seemed beyond doubt even to broadcast journalists themselves. One of them remarked in an interview for my research that “if somebody’s potentially saying that they’re capable of influencing an independent public inquiry into something as important as the Iraq War, that’s hugely significant.” Yet this story was absent from all television news reports from the main providers – BBC and ITN – and received only passing mention as a ‘news in brief’ piece on the BBC’s Newsnight. This marginalisation was broadly reflective of the Guardian’s own coverage in which the story featured only as a relatively minor 300 word article on page 12 of its print edition. For all the resources and publicity that the mainstream media brought to bear on the cable releases, information arguably of the most acute public interest remained confined to the side lines. Two days after the aforementioned cable was released, veteran BBC reporter Jon Simpson made no mention of it in his summing up of the leaks overall:An awful lot of it is really not much more than refined tittle-tattle and the only thing that I’ve really raised my eye brows at is the suggestion – and you’ve got a put a question mark over it – that a Chinese diplomat said to a South Korean diplomat ‘we don’t really care if Korea is united under South Korean control’ […] If true, that is potentially important (BBC Newsnight, 3 December 2010).

This stunning omission was a vivid example of the all too often blunt instrument that masquerades as public service news. The diversion of the media’s spotlight and their unwitting complicity in the crisis management strategies of elites – more than any legal incapacities – ultimately explains the failure of accountability in such cases. They tend to produce public inquiries born in a firestorm of media attention but which invariably burn out with a damp squib. By the end of 2013 it looked as though Chilcott had finally agreed a ‘compromise’ with the government. According to the Guardian newspaper, “extracts of the correspondence are now expected to be published in the report in redacted form” (30 December 2013). But whatever the outcome, these inquiries have exposed deeper tensions between a traditional culture of secrecy within the inner workings of the British state, and a developing culture of transparency. The latter has meshed values of radical openness associated with the digital age, democratic traditions that place emphasis on the accountability of power, and an entrenched consciousness of press freedom among journalists. But rather than producing meaningful transparency, these forces have merely elevated the risk that when it comes to crimes of the powerful, justice will be seen to be done rather than actually done. They have produced spectacles of accountability that ultimately serve comparable ideological ends to the dominant narratives that have long obscured the brutality and injustices of western imperial conquest. Rather than promoting the spread of democracy or a ‘kind and gentle’ empire, the message here is one of a robust and functioning accountability system in which no power is beyond the reach of public oversight and sanction. And it is fast becoming the oldest trick in the book.Justin Schlosberg is a media activist, researcher and lecturer at Birkbeck, University of London, and author of Power Beyond Scrutiny: Media, Justice and Accountability.

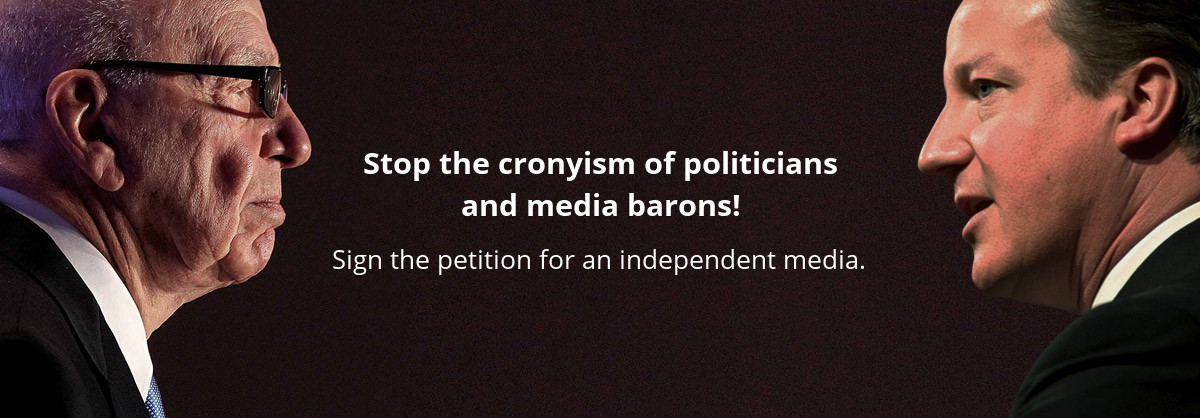

Sign the petition for an independent media.