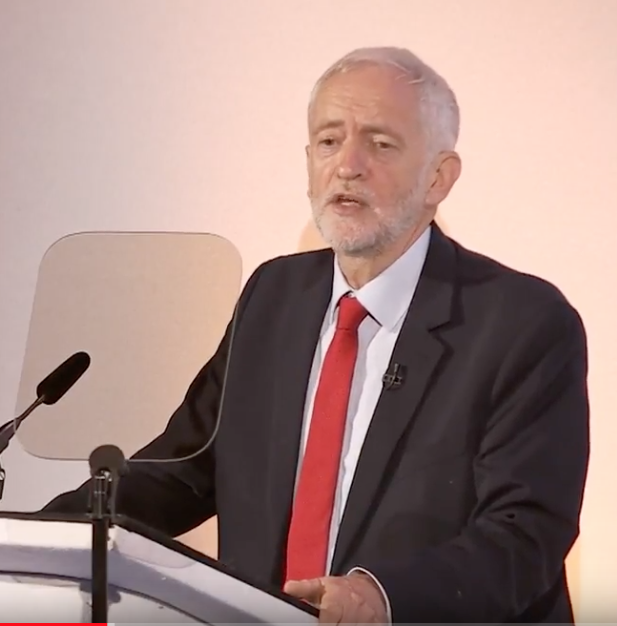

Jeremy Corbyn’s proposals for major reforms to our ‘failing’ media system, outlined in a speech to the Edinburgh Television Festival on 23 August, are much-needed and long overdue.

They lay out the basis for a more accountable and representative media that promotes new sources of independent journalism, demands that the biggest tech platforms make a full contribution to public interest journalism, envisages a far more democratic BBC and seeks to expand FOI to make the private sector more accountable to public scrutiny. All in all, the proposals pave the way for a serious public debate about the rights and responsibilities of some of our largest media outlets and the possibility of a digital future that aims to serve audiences and citizens rather than shareholders and governments.

Some of the proposals dovetail very closely with policies with which we are associated including:

- introducing measures to make the BBC more independent of government and more representative of the population it serves;

- a levy on platform monopolies to support new entrants producing non-profit journalism

- the opportunity for investigative and local public interest journalism to seek charitable status