and why Labour cannot and should not play the mainstream media game

by Justin SchlosbergMyth 1. The mainstream media are all complicit in an orchestrated smear campaign against Corbyn

This is a common inflection among Corbyn supporters who view the coverage of his leadership with deep-seated cynicism and mistrust. But the reality is more complex and more subtle. There are no doubt some professional journalists and editors who have knowingly and willingly used their platform in an attempt to discredit Corbyn’s leadership from the outset. There also likely some who have knowingly and reluctantly accepted the editorial ‘whip’ of their pay masters. But most simply believe that they are covering the stories that matter to their readers or viewers, or to the public at large, and in a way that will resonate strongest with them. They are not necessarily cognisant of the ‘other story’ or the pressures of institutional and cultural conformity that can push their focus in a particular direction. This is important because if we want to try and tackle the problem of media bias, we have to first understand it in all its complexity.Myth 2. There is no mainstream media bias because there is no mainstream media

There are some who believe that we live in a hyper media age where the ability of a relatively small number of ‘mass’ media outlets to shape public debate has dissolved, and that for better or for worse, the digital news agenda reflects the full spectrum of ideas, issues and perspectives on any given news topic at any given time. The rapid growth of ‘alternative’ news channels like thecanary.co is seemingly testament to the fragile and loosening grip of incumbent news brands. But the reality is there is still a vast proportion of the electorate beyond the limits of the Twittersphere and for whom national newspapers and broadcasters have a deep and unchallenged reach. Even online, most of the news consumed on or through the likes of Facebook, Twitter or Google stems from a small number of major players that reach across fragmented audiences.Myth 3. Mainstream media bias does not matter because, if anything, Corbyn’s support has only increased

It is true that the overwhelming editorial attacks on Corbyn since he was first put on the Labour leadership ballot seems to have done little to dent his support. But his critics rightly point to a different story told by national polls which suggest that beyond the grassroots, Corbyn carries little favour with the electorate at large. Indeed, editors have tended to justify their particular news judgements about Corbyn on the basis of these poll ratings. But this assumes that the polls influence the news agenda rather than the other way around. It is particularly telling in this respect that a brief and quiet rise in Corbyn’s approval ratings back in the early spring coincided with a relative calm between media storms triggered by front bench briefings against the Labour leader.Myth 4. Perceptions of media bias are themselves unavoidably subjective

This is another common defence invoked by professional journalists who suggest that those at the losing end of agenda battles will always cry foul over media bias. An equivalence is often drawn in this sense between Corbyn supporters and those of far right political actors – such as Donald Trump and Nigel Farage – who complain equally bitterly about their leader’s treatment in mainstream news coverage. But there are two problems with this position. First, accusations of bias are not the same as evidence of bias. The right-wing press may charge the BBC with a left-wing bias on the basis of conjecture, but this is hardly equivalent to rigorous academic research that consistently and exclusively points to the contrary. Second, Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters are not the polar equivalents to those of Farage or Trump. He was elected on a platform that was predominantly about opposition to austerity and the Iraq War. The suggestion that these political viewpoints are in any way extreme (as opposed to mainstream), or reflect some kind of Trotskyist insurrection, is itself an indication of just how distorted the debate has become. There is a related concern based on the professed political leanings of some of those involved with the Media Reform Coalition (including myself) which produced research on television and online coverage of the recent Labour leadership crisis. Far from undermining the integrity of the research, however, it would have been completely disingenuous for researchers analysing such a contentious issue to not be open about their personal political leanings, and to pretend that the study was not motivated by particular concerns or political perspectives. No research on media bias starts from an entirely neutral or objective standpoint but this doesn’t invalidate any such research. What matters is the steps that were taken to ensure that the potential for subjective interpretations to intervene in the analysis was minimised. In view of the highly charged nature of the topic in relation to the aforementioned study, we were, if anything, overly cautious in our approach and completely transparent about the lengths we went to in order to ensure that the findings were reliable and valid. We also garnered endorsements for the research from 15 of the most senior and renowned media experts from a range of institutions and reflecting a breadth of political perspectives on this issue. This is far more than would ordinarily be required to be accepted for peer reviewed publication. These academics have signed and published a joint letter acknowledging the rigour of the research and the significance of its findings. Some have also questioned why the research was not submitted for formal peer review prior to publication. The answer is simple: peer review is a process that takes months and this research was conducted in response to urgent concerns about the way that the Labour leadership crisis was being covered, with implications for the ensuing leadership challenge and the future of Britain’s largest political party. It would have been entirely irresponsible not to publish the findings of our research in a timely way given the acute political circumstances.Myth 5. Bias is inevitable or unavoidable because Corbyn shuns the mainstream media

This argument has been made repeatedly by journalists within the liberal/left press or mainstream broadcasters and suggests that Corbyn’s media woes have been somehow self-inflicted. But the idea that the coverage might have been qualitatively different had Corbyn engaged more proactively with the mainstream media from the start is at best dubious. Back in the dim and distant past of spring 2015, a front page photo of Ed Miliband making a mess of a bacon sandwich seemed to capture the media narrative at large during the last General Election. The relentless personalised attacks on a leader who did ‘engage’ with the media, and by and large adhered to a neoliberal political consensus, showed the futility of Labour pandering to the Murdoch-Mail press. But there are some who simply assume that the much more savage and extensive negative coverage of Corbyn is a reflection of nothing more than his much greater leadership failings. As the editorial director of the Sunday Times put it on BBC2’s Newsnight programme earlier in the week: “Jeremy Corbyn is not up to it, therefore he gets bad press”. Underpinning this view is an implicit assumption that whilst individual newspapers may peddle particular editorial lines, Fleet Street collectively does not get the story wrong. In a post-Hillsborough, post-Bloody Sunday and post-Financial Crisis world, that seems like a rather naïve and antiquated view. But it also wrongly assumes that the press has gotten their story about Corbyn’s leadership failures straight. In fact, Corbyn has been portrayed almost in the same breath as a weak, ineffectual leader and an all-controlling Stalinist dictator; as a ‘nice guy’ not up to the rigours of mainstream politics, and a ‘nasty’ schemer who knows and plays the game all too well; as a leader too rigidly committed to his personal principles, and a hypocrite or flip-flopper. And this is the central point missed by the likes of Owen Jones who have argued that the lack of a meaningful strategy of engagement with the mainstream media has prevented Corbyn from reaching out beyond his base. Embedded in this view is the idea that a Labour leader can and should play the mainstream media at its own game. But this not only risks falling into the trap that destroyed Labour’s ‘electability’ under Miliband, but also absolves journalists – especially broadcasters and the liberal/left press – of their responsibility to look beyond Westminster and the machinery of media management synonymous with the Blairite era. The suggestion that journalists were somehow prevented from telling the whole story because Corbyn chose not to engage with them is a particularly insidious form of media logic that considers issues or perspectives only newsworthy if they are handed to journalists on a plate, preferably exclusively or via the kind of anonymous briefings that convey a false sense of drama and authority, whilst allowing political actors to engage in smear tactics behind the cloak of invisibility. Whoever wins the Labour leadership ballot must recognise that yielding to such media pressures is a false economy.Join us on 15 September to discuss the media, the movements and Jeremy Corbyn

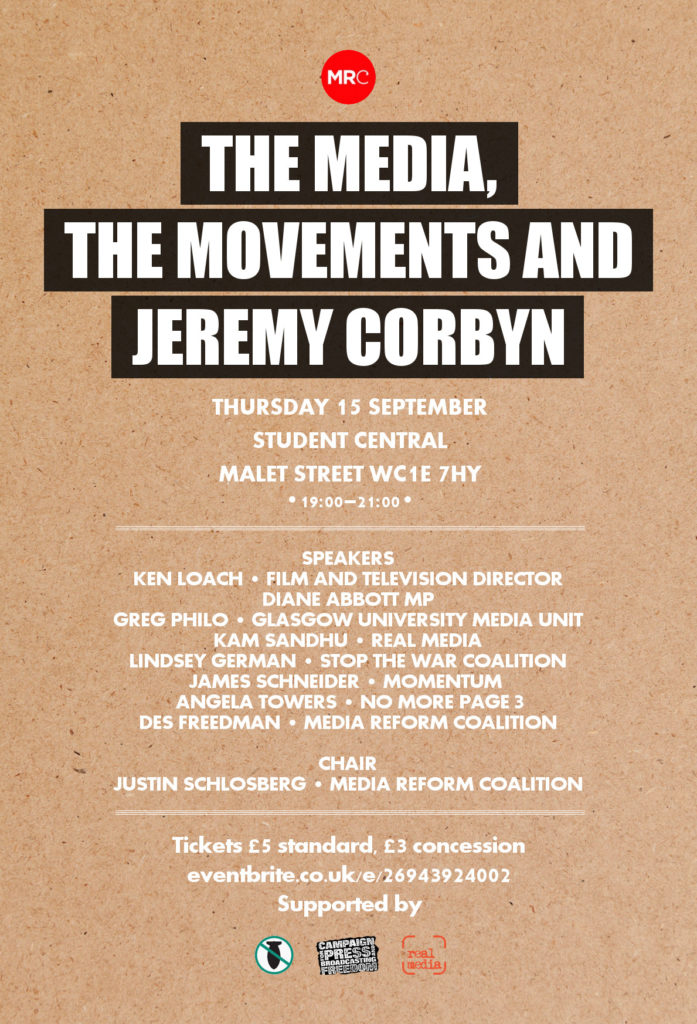

As part of the Media Reform Coalition’s ongoing campaign for a media that informs, represents and empowers the public, this event will bring together media activists, workers and scholars to explore the media’s misrepresentation of progressive movements and voices and shape a response that does them justice. Speakers: film and television director Ken Loach, Diane Abbott MP, director of Glasgow University Media Unit Greg Philo, co-founder of Real Media Kam Sandhu, convenor of Stop the War Coalition Lindsey German, national organiser of Momentum James Schneider, No More Page 3’s Angela Towers and Des Freedman of the Media Reform Coalition. Chair: Justin Schlosberg, Chair of the Media Reform Coalition When: Thursday, 15 September 2016 from 19:00 to 21:00 Where: Student Central, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HY, United Kingdom – View Map Tickets: Eventbrite, £5 standard, £3 concession